Monthly Archives: October 2013

Right to Reject: But What About the Practicalities?

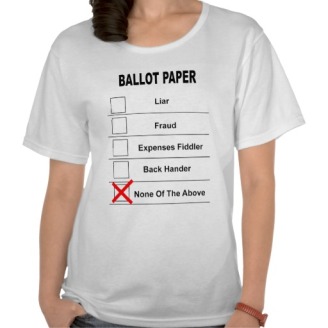

The Supreme Court has directed the Election Commission to give the voters an option of ‘none of the above’ in ballots. Image courtesy zazzler.com

The Supreme Court of India has been a favourite of the country’s citizens. In an age where the 1.3 billion of us are almost fed up of the legislature and the executive, our faith has naturally come to rest upon the judiciary, spearheaded by an actively involved Supreme Court. In recent years, some of the verdicts of the Court have reiterated the demands (both silent and vocal) of the general populace. We wanted someone to hold scamsters accountable for their actions, and the Supreme Court quashed all the licenses issued under the now infamous 2G spectrum. We wanted the system to be rid of criminals and the Supreme Court allowed for convicted legislators to be disqualified and banned. It’s almost like the Supreme Court has been in our corner in our no-holds barred sparring contest against the other two organs of the state. Hence, people naturally assume that the recent decision by the Court – that gives the voters in the country an option of not voting for any candidate in an election – has to be landmark and ground-breaking. The media coverage of the verdict gives the impression that it is the best thing to have happened to the Indian electoral system since sliced bread electronic voting machines. However, a closer examination of the decision reveals that the reality might be slightly different.

First of all, let me clarify that I am all for the ‘Right to Reject’ for a voter. Like the SC said in its decision, if MPs and MLAs have the right to abstain from voting in the House, then the voter needs to be empowered as well. Now, I agree that the context of voting in the House and for the House is quite different but the fact remains that the voter needs to have the right to vote for the candidate he chooses, and not the candidate that he is being forced to choose. It is a very important distinction. Most of the times, we- the voters of India, choose to vote for a certain candidate because s/he is simply ‘the best option’ from the rotten lot we have been provided by our loving political parties. With the right to reject, we stand to change that. However, for that, this right needs to be exercised in its purest form. If diluted, it shall negate the very basis for its existence.

The ‘none of the above’ (NOTA) option, which the Supreme Court has provided for now, is something that is in practice in several countries around the world (most notably in Poland, students’ unions in the UK, and some constituencies in the United States). It is a practice that aims to force the political parties to introduce clean candidates, who are acceptable to the voters. There is certainly ambiguity in the definition of clean, but nobody can deny the fact that if the voters are empowered more, it paves the way for a more powerful and better functioning democracy. However, that is only possible if this NOTA option, or this Right to Reject, is successful in achieving its stated goal. The provision has a simple principle behind it- when the voters will reject the candidates put forward by the parties, they shall be forced to acknowledge that their candidates are not acceptable to the general public, and in order to win back their favour, they will have to present better candidates.

In the film ‘Brewster’s Millions’ (1985), millionaire Monty Brewster enters the New York Mayoral electoral race urging a vote for “None of the Above.”

The only problem with this plan is the current silence of the Indian machinery on how the system will be implemented. Neither the SC, nor the Election Commission has clarified whether the votes polled in the ‘none of the above’ option will be counted or not. If they are not counted, then the entire purpose of having that option is defeated. In that scenario, choosing none of the above is just as good as not voting at all, as both the actions will have no consequence on determining the winner of the elections. Suppose, in a constituency of 100,000 registered voters, there is 60% turnout in an election i.e. 60,000 people vote. If 10,000 of these choose none of the above option and their votes are not counted, then the election is effectively being decided by the other 50,000 votes. In doing so, we will have turned the Right to Reject from a hero to a villain, because this way, instead of forcing the political parties to put forward better candidates, it will effectively silence those who are rejecting the candidates. Their choice will have no bearing on the election and hence, their opinion will cease to matter. That, my friends, is not a good example of a democracy.

However, chances are that the votes polled for the ‘none of the above’ option will, in fact, be counted. This clears some confusion, but creates a whole lot more. In order to understand what that confusion is, let us revisit the election in our fictitious constituency. Again, there are 100,000 voters with a 60% turnout i.e. 60,000 votes cast. Say, there are 8 candidates vying for the voters’ attention, who poll a total of 42,000 votes. Candidate A ‘wins’ the election with 15,000 votes as compared to candidate B who polled 10,000. However, one has to see that as many as 18,000 people chose ‘none of the above’. In short, more people rejected all the candidates than the number which voted for any one of them. If ‘none of the above’ was the ninth candidate, it would have won the election. This can be interpreted to imply that the voters would rather have none of these candidates represent them than go for any one of them. Again, the machinery is silent about what happens in such a situation. And mind you, it is not exactly a far-fetched situation. The growing discontent and disenchantment of the voting class with the political class means that this is a very likely scenario.

One of the suggestions doing rounds is that in case the ‘none of the above option’ polls the highest number of votes (or a certain pre-determined percentage of votes) in an election, the entire election in that constituency or for that seat will have to be re-done with fresh candidates. This suggestion uses the rationale that since the public isn’t ready to accept these candidates; the parties must come up with new ones. This is the only way the voters’ ‘right to reject’ will be exercised in a timely manner. Now, while this is a theoretically correct and seemingly correct suggestion, there are certain practical difficulties around it. First of all, elections are a costly affair. Declaring the results null and void and going through the entire process again for a constituency will certainly burden the taxpayers, even if it is the right thing to do. Secondly, the process will not be instantaneous. Parties will need to be given time to nominate their candidates, these candidates will have to be checked and verified by the EC, canvassing and campaigning will have to be done again, followed by the actual polling and counting. The actual time taken will depend on the scale of the election but it will normally run in weeks, if not months. These are certain practical aspects of this provision that need to be addressed if the real benefits of it are to be reaped.

Elections in India are a grand affair, involving hundreds of millions of voters. It will be difficult to hold re-elections in multiple constituencies. Image by Reuters © Tom Heneghan

The truth is that the Supreme Court decision is not the final nail in the coffin for corrupt candidates, not by a long shot. There are a number of issues that plague this option, and a number of questions circling it. Until and unless these issues are sorted and these questions answered, the ‘landmark’ right to reject will remain just a pretty sounding but eventually ineffective proposition. The bottom line is that even though the right to reject is a wonderful new change that promises to transform the Indian electoral and political system, there are a number of practical issues that need to be addressed before it can be enforced. Unless these issues are sorted out at the soonest, the right to reject remains toothless. The coming Assembly elections in Delhi, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, etc. will serve as the litmus test for the right to reject. Let’s all hope that the powers that be are able to come up with a feasible method to enforce the right to reject through these elections, so that it can be effectively implemented when the big guns come out. (read: Lok Sabha 2014)